It’s 10 o’clock on a beautiful May morning, and Josefa Tur Torres from Ca n’Esperança is waiting for us with her niece, Antonia Torres Marí from can Cova Camp, at the door of the village church. While we wait for the rest of the group to arrive, Josefa, who is in her nineties and full of vitality, tells us how she and her niece were both born in the house just opposite us that is now being renovated. They recall how they both came into the world in the same room, although of course the times were not the same, because Antonia belongs to a later generation.

Soon we are joined by David Reartes, the renowned chef from Lips Reartes at playa d’en Bossa beach, and the real instigator of this encounter, who explains how the idea came about of compiling a book on the island’s botanical riches before the folklore amassed by people such as our guides, Josefa and Antonia, falls into oblivion.

As we are walking towards the village bar to have a coffee before our country walk, we are joined by the two experts who will accompany us to ensure that all of the herbs that belong to the local folklore are correctly documented with proper scientific rigour. They are Jaume Espinosa Noguera, a pharmacist and botanist, and, he stresses, “an environmental educator”, and Mario Stafforini, a well-known artist and “amateur” botanist, who trained as an architect. “Amateur” is how this painter describes himself, but we will soon discover that he is in fact a walking botanic encyclopaedia.

Now that everyone is here, we quickly drink up our coffee, introduce ourselves, and prepare for our walk in search of herbs to catalogue.

Our group

But our attention remains focused on the matter at hand, which is to enjoy a walk under a clear blue sky looking for herbs. We don’t have far to walk before coming across the first plant that catches Antonia’s eye. Known locally as Llitsó, a name that comes from “leche” (“milk” in Spanish), like lettuce, because it is also a milky plant like its domesticated cousin (“hare’s lettuce” or “sow thistle” in English). “We used to eat this in salad”, says Antonia, while Jaume adds the scientific note by pointing out that “this is one of the most abundant plants on Ibiza, it grows all over the island, even in urban areas”. It is Mario Stafforini who gives us the plant’s scientific name (Sonchus tenerrimus), and adds that it is a plant that “was eaten throughout Europe”. Josefa also recalls that they used it for salad and that it was very tasty, because “the people of Ibiza were poor but they were very particular, and they used to eat this but only in season and where the soil was fertile”, she says. Mario adds that it can also be eaten cooked and that is often used to feed rabbits, but as we all know, “if it’s good for rabbits it’s good for people”. Antonia reminds us that “it is now dying off, but where there is water it grows all year round. We used to dress it with oil and vinegar like salad”. David listens to all these explanations with the ear of a diligent student.

Mario Stafforini

Meanwhile, we watch as Mario walks off a little way and then comes back with a green leaf that means nothing to novices like us, but that turns out to be quite a delicacy. “Chicory”, he says, “you pull the leaves off and put them in salad and mixed with lettuce it’s delicious”. Once again each member of the group contributes their grain of wisdom and so we discover that what we have before us is camarrotja in Catalan, its scientific name is Cichorium intybus, and it was eaten regularly. Growing next to the chicory is Reichardia pricoides, the leaves of which are far too alike for inexperienced botanists such as we, and turn out also to be extremely tasty.

We have not gone more than 100 yards and we already have a recipe for salad: Sonchus tenerrimus, Reichardia pricoides, Cichorium intybus with some lettuce leaves, oil, vinegar and salt. A delicious treat.

But on our way we not only find plants to appease our appetite, we will also find plants to prevent prostate cancer, bushes to care for hands damaged by the rigours of work at sea, plants that we can use as brooms, and even herbs to feed the spirit. And that, despite the fact that this is not the best time of year, “the best months are February, March and April”, points out Antonia. “Yes,” says Josefa, “everything is beginning to die off and in a fortnight there will be nothing left”. Besides which, “there has been very little rain this year”, adds Mario.

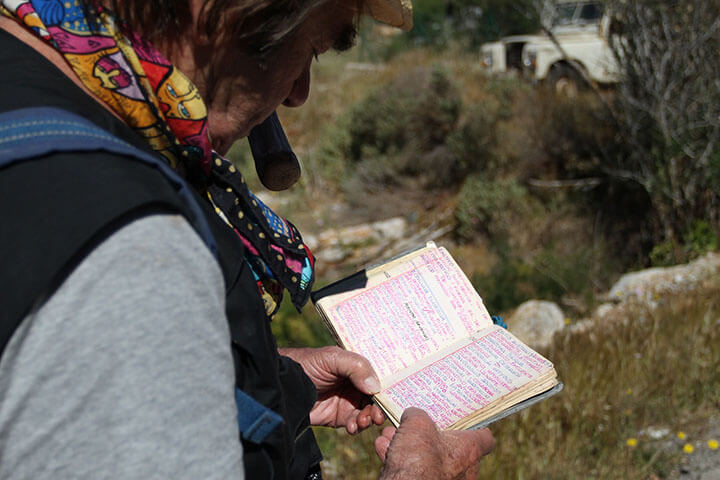

But Jaume does not seem concerned and is absorbed in the surroundings, collecting plants, asking our guides, supplying information at such a speed that it is impossible to take it all down. Spontaneous working groups are formed and so we see how Mario checks his field book (worthy of a museum) against the knowledge of the locals, while Jaume explains the properties of one plant or another to David. The discovery of a specimen of pericó or herba de Sant Joan (Hypericum perforatum) —St. John’s Wort in English— brings everyone back together around the plant, for this is a medicinal botanical species “par excellence“, according to Jaume, and let us not forget that these are the words of a pharmacist specialising in botany. This is a photosensitive plant that in sunlight takes on an intense red colour that dyes everything to which it is added. Its properties are well known to the pharmaceutical industry and it is sold in capsules and prescribed for depression, among other uses. But we continue a little further and come face to face with Thapsia garganica, a plant that is being studied as a treatment for prostate cancer. It grows in abundance and is one of the most characteristic plants of Ibiza and Formentera. Following on from these discoveries, the Aloe vera that the tireless Josefa brings us seems quite ordinary. At this point we would like to add that the agility of this 91-year-old woman left the entire group —except her niece who has known her all her life— openmouthed. Taking advantage of the fact that her house was not far from where we were walking, she said she would pop in for a moment to show us the Aloe vera growing there, and the grace and speed with which she completed her task were amazing. In less than two minutes she was on her way back at the speed of a Spanish legionnaire, with the plant in her hands, smiling and proud of the admiration that her fitness was arousing.

Jaume and David observing a Thapsia Garganica

They also showed us the marigold (Calendula officinalis), the seeds of which contain an oil with healing properties that are similar to those of aloe. It can be used to treat bruises, stings and bites, burns and other minor skin injuries. At this point, referring to her aunt, Antonia asks us: “How do you think she has lived to over 90 in such good health? We started going to the doctor after my mother died, before that we never went”.

Before our walk is over there is still time for us to listen to any number of anecdotes about the old days when there were two schools in the small village, one for boys and one for girls, and many people used carob tree beans as food. The old days when “the bread was bad”, according to “Aunt Pepa”, which is the name with which by the end of the”expedition” the whole group is addressing this elderly woman who through her own merits has become its supreme commander.

The time has come to take our leave and we decide to say goodbye where we began, that is to say, in the bar, but accompanied now by a glass of beer. As we are on the point of going inside, a nearby garden catches the eye of our apothecary, where he sees a splendid poppy (Papaver somniferum) that is at its peak, a variety that is known on the island as cascall, and is the very same flower from which opium is obtained. Although its use is now illegal, “Aunt Pepa” and Antonia say that at one time it was a common remedy for easing toothache or helping children to sleep. Mario tells us how it can be used to ease pain or for other more recreational purposes. And so ends with these explanations around the table a pleasant morning which we all agree to repeat when the countryside is next at its finest and can show us all its riches.

Opium poppy